Making DAOs Work

Insights from our literature review on DAOs and labor

In our previous post we announced the beginning of our project exploring web3 as a work environment. Here we present the insights from the first phase of our research surveying the existing relevant literature on the topic.

Authors: Laura Lotti, Nick Houde, Tara Merk

We began our inquiry in the web3 work environment with an extensive literature review comprising three phases:

In the first round, we focused on academic and industry analyses of blockchains, DAOs and work in Web3 aiming to get a comprehensive overview of existing studies and understandings of DAOs as a work environment;

In the second round we mapped the fragmented landscape of DAO work to identify the primary elements that make up the human, organizational, conceptual and technical dimensions of this ecosystem and looked at literature in organization and management sciences, and institutional analysis for theoretical frameworks that would enable us to engage with the complexities of DAOs;

Lastly in the third round, we explored historical and contemporary non-DAO analogs for workers’ organizing that may provide useful models to think about “social security” in web3 context.

You can find our full annotated literature review here. Below we discuss the key insights from each phase that form the point of departure for our ethnographic research.

1. What is DAO work?

What does it mean to work for a DAO? To begin making sense of this complex phenomenon we drew on existing literature, anecdotal evidence, and conversations with DAO leaders and operators to model what constitutes DAO work and how we might go about framing subsequent ethnographic research down the line. Our review included academic articles on DAO labor and protocol related research, crypto news articles, blog posts, industry surveys and reports, and painstakingly combing through various DAO governance forums to identify relevant discussions and proposals. In doing so, we set out to answer the question: Are DAOs really the future of work? Or are they just a glorified form of gig labor?

Indeed, DAOs have been celebrated as “the future of work” due to their flexible organizational environment based on open membership and collective ownership via tokens (Wilser 2022, Salmond 2022, Jesuthasan and Zarkadakis 2022). But as the multitude of existing DAOs demonstrate, there’s not just one future of work inlaid in the idea of DAOs. From large-scale token-mediated protocols to human-centric organizations more akin to companies with on-chain elements, this organizational framework is being deployed in wildly different ways.

Furthermore, as the space keeps evolving, the range of work that happens within DAOs is very diverse in both content (from code, to administration, community management, design, decision making, etc.) and form (e.g. bounties, project, full-time employment). For instance the Gitcon and Bankless survey of 2021 highlights that the majority of DAO work has to do with “keeping the lights on” (including activities such as community management, operations, marketing and governance), countervailing the early narrative of blockchain as an environment primarily inhabited by cypherpunks and open source developers.

In short, just as the creator economy has turned every piece of media into “content,” DAOs have turned any type of work into “contributions,” often without a critical understanding of what this flattening out implies. Because of this, mapping the experience of contributing to DAOs is becoming increasingly crucial for understanding how and in which way DAOs could or should impact the future of work for the better.

An illustration of what collapsing this diverse work environment to “DAOs”, “Contributors” and “Contributions” does, that is heavily inspired by previous work in the “After the Creator Economy” zine.

Since the “DAO boom” of 2021, several other initiatives have started to analyze the working conditions of operators and contributors to the web3 ecosystem. Beyond the already mentioned Gitcoin/Bankless (2021) survey, Tally (2022) and ValuesIndex (2022) report that core challenges faced by DAO contributors are: unstable compensation (especially for non-technical skills), difficulties in navigating a decentralized work environment, and unclear on- and off-boarding issues, amongst others. MakerSES’s research in decentralized workforce (2022), on the other hand, focuses on the issue of technical talent retention through market cycles, highlighting that while vision and community play a key role in attracting people to the ecosystem, the lack of clarity around how to contribute and the complexities of this novel work environment are some of the key factors that lead people to leave the space.

These online surveys are a great tool to gain a high level understanding of the major issues that DAO contributors face. However they suffer a few limitations. First, most surveys don't distinguish between the different types of contributors (e.g. employed by the DAO vs hobbyist contributor vs freelancer) with respect to the contribution models of a specific DAO (how its value flows). Second, they do not allow for in-depth conversation that can sensitize us to the assumptions about how contributions, motivation, and value operate in this unique terrain. Third, and most importantly, surveys do not open a space for discovery of what mechanisms and working models are missing, such as social security or welfare mechanisms that would offer different forms of incentives to contributors than compensation alone, making DAO contribution a viable long term option for work. In other words, these surveys confirm a few assumptions about the overall state of DAOs but they do not provide actionable findings.

2. Organizational archetypes and the complex environment of DAO contributors

Throughout our initial review, we recognized that different articles invoked a variety of concepts, images, and metaphors relating both to DAO contributors and DAOs as organizations, as well as a variety of tools and technologies that mediate the relationships between them.

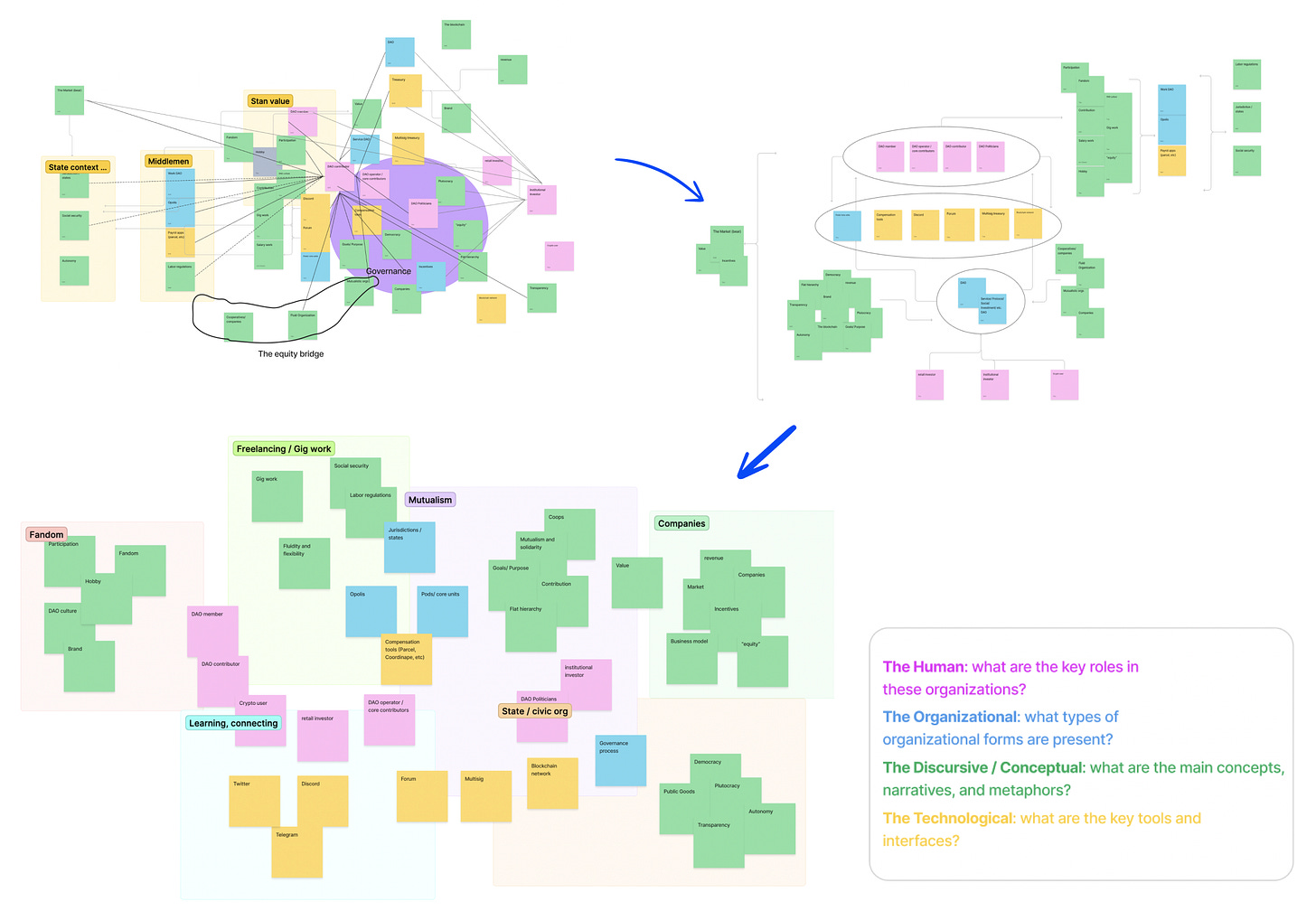

We drew on situational mapping (Clarke 2011) to begin making sense of the complexities of the DAO work environment. We mapped out the human, organizational, discursive/conceptual, and technological elements that make up the DAO landscape. Beyond the array of tools and roles, a large part of the mapping involved the vast, and often conflicting, ideological, and discursive ecology around DAOs. Unlike more defined structures for working, DAOs present the unique challenge of combining web3 technologies with the organizational models and discursive elements of firms, start-ups, mutualist organizations, funds, educational institutions, or even fan clubs. Situational mapping helps us see how, why and when these more defined frameworks for work can be used as analog reference points for DAOs. Through this process, we came to the conclusion that in order to approach the study of DAO contributor experience, we need to address a more fundamental question: how can we most effectively frame the web3 work environment without missing any of the richness and diversity of its dimensions?

So we mapped, and mapped and mapped until we got to a somewhat coherent picture of the DAO landscape.

In academic literature token-mediated protocols have been discussed as an example of fluid organizations — that is, organizations “characterized by continually changing templates of boundaries, decision-making, and task and role allocation” (Schirrmacher et al. 2021). But as our “messy” situational mapping makes clear, DAOs are not only characterized by fluid structure. They are also examples of hybrid organizations, which combine multiple identities, forms, and institutional logics (Battilana et al. 2017) under a single organizational umbrella. While hybrid organizations have been studied primarily in the context of private-public partnerships (Jay 2012, Smith and Besharov 2017, Bogenhold and Klinglmair 2016), this framework fits DAOs well.

DAOs can be seen as hybrid organizations because, beyond the strictly defined logic of the protocol, they often do not have a single, clearly defined, institutional logic. Rather, they host a multiplicity of competing and conflicting narratives and institutional logics that come from the demands from the varied stakeholders: the token holders (“number go up”), the contributors and core team members (compensation and work environment, not going to jail), the discourse and self-fulfilling mythology of the space (“decentralization” etc.), public perception (“public goods”, “democratic decision making”), and finally regulatory scrutiny and societal improvements (legitimization, actual public goods etc.). These overlapping and at times conflicting social imaginaries have previously been researched at the protocol layer (Swartz 2018, Brody & Couture 2021, Dylan-Ennis et al. 2023), but they remain underexplored at the application /DAO layer.

The pro-social imaginaries of DAOs and web3 have played a key role in attracting contributors to the space. Yet, in the current market conditions, that vision is at risk of falling apart, when the space has been unable to provide the type of public goods mechanisms and social security needed for everyone to weather the storm equitably. Thus, rather than shoehorning DAOs into a single analytical frame or organizational imperative (whether profit-oriented or pro-social), it may be more productive to approach them as instances of hybrid forms in order to answer questions such as:

What are the competing institutional logics occurring in the DAO ecosystem?

How do they affect and shape contributors’ experiences?

How do these change the organizational environment itself?

What tensions and paradoxes do these generate?

How can hybridity be harnessed in the most beneficial ways for all the constituencies involved?

These questions form the basis of the analytical framework used in our current ethnographic research.

3. Improving web3 work by learning from non-DAO analogs

After parsing the complexities of the web3 work environment, we have been conducting analysis of historical analogs (e.g. mutualization and social welfare mechanisms) which are not easily ported to the web3 contributor ecosystem, but which contain potentially relevant insights and useful metaphors. We looked extensively into the history of mutualist organizations, social insurance, and cooperatives. We then paired this with contemporary studies about fandom and the creator economy as new models for work, effects of corporate philanthropy and corporate social responsibility on employees’ wellbeing, the work environment of the non-profit sector, as well as the familiar challenges and opportunities of the platform economy and digital labor. Our goal was to answer the question: what do financial and job security mean in these different organizational contexts? What explicit or implicit mechanisms do they draw on? And what do they solve for?

Our analysis showed that, beyond the statutory social security provided by national jurisdictions, different types of organizations operationalize the concept of security in very different ways. For fandoms and political organizations, security is broadly associated with the longevity of interests and ideologies. Yet, for coops and mutualist organizations security primarily revolves around minimizing financial risk, which is achieved through various pooling mechanisms such as in-network financial services and employee swaps. Additionally, in both for-profit and non-profit entities, employee wellbeing can be interpreted as a form of security, which is performed through the reproduction and enactment of discursive commitments at the foundation of an organization’s mission or philanthropic initiative. These approaches serve as soft mechanisms to enhance intrinsic motivation, promote alignment among employees, and bolster the organization's image and reputation among external stakeholders. Voluntary standards, such as organizations' manifestos and principles, also play a key role in providing robust normative frameworks with a social orientation.

Out of this multitude of meanings and mechanisms, we distilled four main archetypes of “solidarity primitives” that inform our thinking as to what the basic building blocks of concrete social security mechanisms in web3 consist of:

Alliances between DAOs and contributors that enable the sharing of labor and access to special network services, such as in-network employee swap and insurance funds

Bridges – that is, intermediator tooling and organizations that enables interoperability between DAOs

Anchors, performing an analogous function to bridges, but focused on providing an interface with different legal jurisdictions

Voluntary standards and strong social norms that provide good faith minimums for working conditions at the ecosystem level

We’ll discuss these models in more detail in a following post. Coupled with the findings from the ethnography, this top level survey of historical analogs informs the next phase of our research, focused on understanding and addressing the challenges of social security, talent retention, and longevity through a practical lens.

Based on these initial findings, we are structuring our research around three hypotheses that we believe will afford more clear paths forward for actionable knowledge and mechanisms development for better contributor experience:

🛤 Aligning organizational archetypes in DAOs unlocks how people perceive and structure their participation.

The stated purpose of DAOs often differs from how they operate. Yet the organizational metaphors used to understand DAO work have a significant impact on how people contribute to DAOs and what they see as criteria for added value. Comparing DAO work to familiar categories such as gig work, freelancing, open source development, or shareholding can limit our understanding about the unique characteristics of DAOs, preventing us from fully appreciating the potential of this form of work while creating misalignment between the organizational structure and the contributors, leading to exhaustion, interpersonal governance issues, and apathy.

⏳ Many of the challenges faced by DAO workers and DAO organizational structures have historical and non-web3 antecedents. We can learn from past use cases and existing solutions.

After reviewing research about mutualist organizations, funds, start-ups, and firms, a number of challenges have striking similarities to the ones expressed by DAO contributors. Translating these historical learnings into the unique context of the DAO ecosystem will accelerate our ability to adapt and find solutions; learning from experience rather than starting from zero.

📈 How work is valued and structured has a strong impact on talent retention, labor market volatility, and the succession problem.

Social security mechanisms, insurances, and other benefit structures are not only about safety nets; they also provide for essential incentives that organizations need to retain and maintain talent. Similarly, the long term health of an organization is oftentimes correlated with their ability to transfer institutional knowledge and mitigate labor volatility which can be a drag on productivity.

What’s next…

Inspired by the practice and method of Worker’s Inquiry, we’ve been conducting 21 in-depth ethnographic interviews as well a 3-hour IRL focus group with 22 people working in DAOs and web3 to map how these insights and metaphors from our research squares with the day-to-day experience of DAO contributions. In doing so, we aim to have a more profound sense of existing social mechanisms and value flows that underpin this contributor experience. This is the first step to developing new strategies for approaching contribution while guiding us in the development of web3 mechanisms that might satisfy the needs that legacy social security have served in other sectors or ecosystems. In our next post, we’ll share the findings from our ethnographic work.